Titanic's Morse Code: How Operators Saved 705 Lives

On the freezing night of April 14-15, 1912, two young radio operators worked frantically in a cramped cabin aboard the RMS Titanic, their telegraph keys clicking out a desperate rhythm that would echo through history. While most remember the Titanic for its tragic sinking, fewer know the heroic story of how Morse code—and the two men who operated it—saved over 700 lives that night.

This is the dramatic tale of Jack Phillips, Harold Bride, and the life-saving power of Morse code communication in humanity's most famous maritime disaster.

The Marconi Men

Twenty-five-year-old Chief Telegraphist Jack Phillips and his 22-year-old assistant Harold Bride weren't technically employed by the White Star Line. They were "Marconi men"—wireless operators employed by the Marconi Company, which provided telegraph services to ships.[1] Their primary job wasn't safety communication but handling "Marconigrams": personal telegrams for wealthy passengers conducting business or sending messages to friends ashore.

In the five days since leaving Southampton, they had transmitted over 250 messages, working around the clock in three-room quarters they called "The Marconi Room."

To transmit Morse code at the required 40 words per minute, both operators had undergone extensive training. Their fingers flew across the telegraph keys, translating thoughts into the dots and dashes that defined maritime communication in 1912. Little did they know that their Morse code skills—practiced daily on routine passenger messages—would soon be tested in the most dramatic circumstances imaginable.

If you're interested in learning how to send and receive Morse code messages like these operators did, visit our Morse code translator to practice encoding and decoding messages with instant audio playback.

The Ignored Warnings

Throughout April 14th, multiple ships transmitted ice warnings in Morse code to the Titanic. At 9:00 AM, the Caronia warned: "WESTBOUND STEAMERS REPORT BERGS GROWLERS AND FIELD ICE." At 1:42 PM, the Baltic sent details of large icebergs ahead. More warnings arrived throughout the day.[2]

Phillips dutifully delivered some warnings to the bridge, but the wireless equipment had experienced technical problems earlier, creating a backlog of passenger messages. The operators were working overtime to catch up—handling revenue-generating traffic took priority over routine ice warnings in calm seas.

The most fateful ignored warning came at 11:00 PM from the nearby Californian: "SAY OLD MAN WE ARE STOPPED AND SURROUNDED BY ICE." Phillips, exhausted and irritated by the loud interruption from such a close ship, responded curtly: "SHUT UP SHUT UP I AM BUSY I AM WORKING CAPE RACE."

Forty minutes later, at 11:40 PM, the Titanic struck an iceberg.

"You Had Better Get Assistance"

Within minutes of the collision, Captain Edward Smith assessed the damage and realized the "unsinkable" ship was doomed. Around midnight, he entered the Marconi Room and gave Phillips and Bride a simple, chilling instruction: "You had better get assistance."[3]

Phillips immediately began transmitting the international distress signal he knew best: "CQD CQD CQD DE MGY MGY MGY." In Morse code terminology, "CQ" meant "all stations" (a general call to everyone), "D" indicated distress, and "MGY" was Titanic's call sign. The familiar pattern of dots and dashes pulsed out into the night:

-·-· --·- -·-· -·-· --·- -·-· (CQD CQD CQD)

He also transmitted their precise position: 41.44N, 50.24W. This coordinate, tapped out in Morse code, would prove absolutely crucial for the rescue that followed.

Harold Bride, waking from his bunk, rushed to assist. Legend has it that at some point during the increasingly desperate situation, Bride half-jokingly said to Phillips: "Send SOS. It's the new call, and it may be your last chance to send it."[4]

SOS (··· --- ···) had been adopted internationally in 1908, but most operators still defaulted to the older CQD. The Titanic became one of the first major disasters where both signals were used, alternating between the traditional and the new.

Curious about the history and development of these crucial distress signals? Explore our comprehensive guide on the complete history of Morse code to learn how SOS and CQD evolved and why they remain important today.

The Race Against Time

As lifeboats began loading, Phillips and Bride worked in shifts, maintaining a constant stream of Morse code transmissions. Multiple ships received their calls:

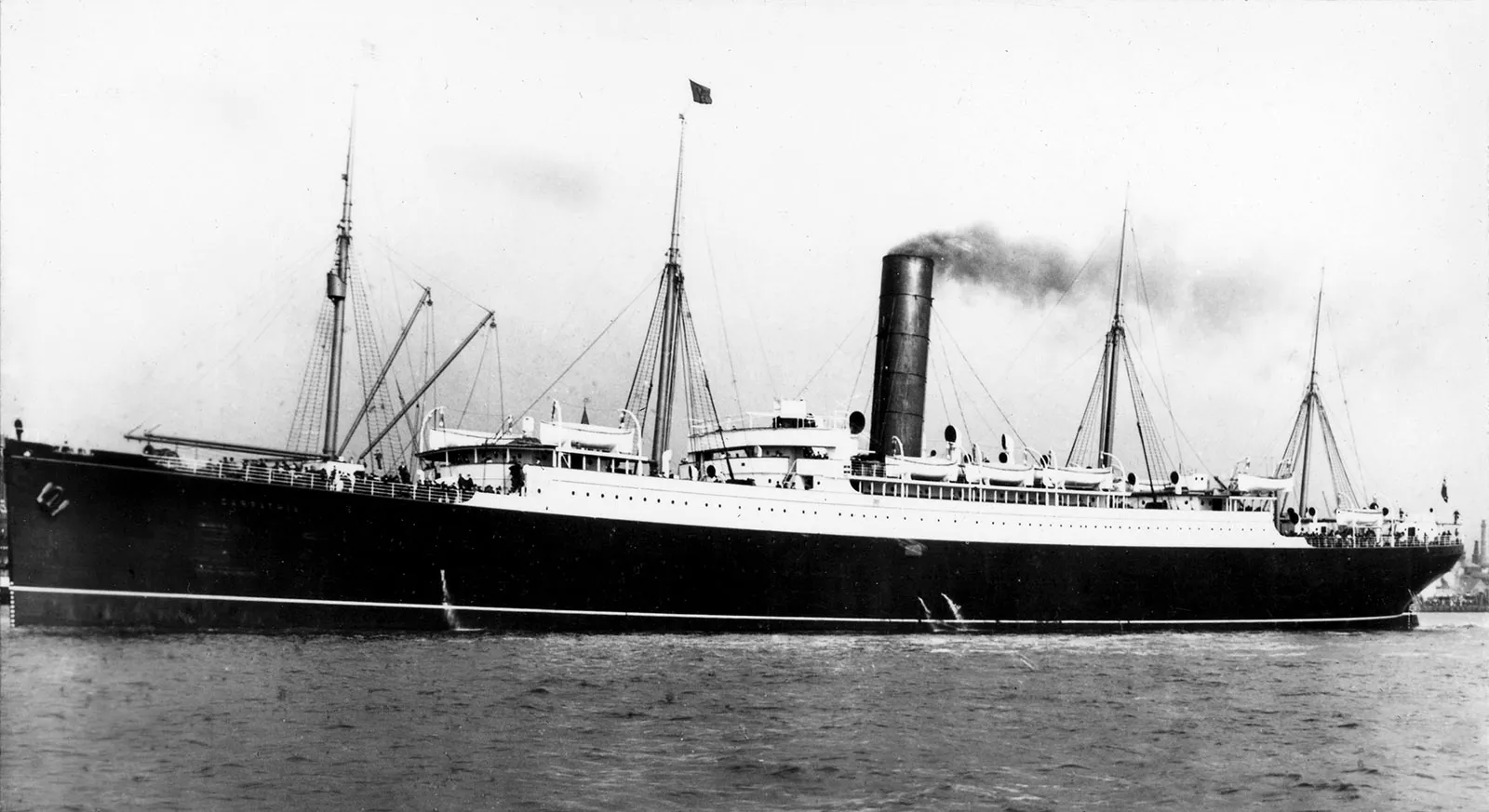

The Carpathia (58 miles away): At 12:25 AM, Harold Cottam, the Carpathia's sole wireless operator, was still awake finishing paperwork—a fortunate coincidence. He received Phillips' transmission: "COME AT ONCE WE HAVE STRUCK A BERG." Captain Arthur Rostron immediately ordered maximum speed toward the Titanic.[5]

The Frankfurt (170 miles away): Responded but kept asking for clarification, frustrating Phillips who famously replied: "THE HELL WITH YOU OLD MAN." Distance made rescue impossible anyway.

The Olympic (500 miles away): Titanic's sister ship received the call but was too far to help. However, her powerful transmitter helped relay messages to shore stations.

The Californian (10-20 miles away): Tragically, their radio operator Cyril Evans had shut down the wireless and gone to bed just minutes before the collision. The Californian could have reached the sinking ship in time to save everyone, but without someone monitoring Morse code transmissions, they remained unaware until morning.

This highlights a crucial lesson about the importance of continuous monitoring in emergency communications. If you want to understand how Morse code continues to be relevant in modern emergency situations, read our article on 10 practical modern uses for Morse code.

The Final Transmissions

As water rose through the ship, Phillips remained at his post, his fingers continuing their desperate rhythm on the telegraph key. At 12:40 AM, the Carpathia responded with perhaps the most welcome Morse code message of the night: "PUTTING ABOUT AND HEADING FOR YOU. EXPECT TO ARRIVE IN FOUR HOURS."[6]

Phillips' transmissions grew increasingly urgent:

1:48 AM: "COME AS QUICKLY AS POSSIBLE OLD MAN THE ENGINE ROOM IS FILLING UP TO THE BOILERS"

By 2:00 AM, the ship's power was failing, reducing transmission range. Captain Smith entered the wireless room one final time around 2:10 AM and reportedly told the exhausted operators: "Men, you have done your full duty. You can do no more. Abandon your cabin. Now it's every man for himself."

Eyewitness accounts differ, but many survivors reported seeing Phillips still at his post, still tapping out distress calls, even after this order. His last confirmed transmission was around 2:17 AM—just three minutes before the Titanic's final plunge.

The dots and dashes fell silent. Jack Phillips, who had worked his telegraph key until the very end, did not survive. He was 25 years old.

The Miracle of 705

Harold Bride survived by clinging to an overturned lifeboat, suffering from frostbite and injured feet. When the Carpathia arrived at approximately 4:00 AM—guided by those precise coordinates Phillips had transmitted—they began rescuing survivors from lifeboats.

Without those Morse code messages, the Carpathia would never have known where to look in the vast, dark Atlantic. The 705 people rescued owe their lives directly to wireless telegraph communication and the two operators who remained at their posts.

Aboard the Carpathia, despite his injuries, Bride insisted on helping their exhausted wireless operator send survivor lists and news of the disaster. His detailed account of the night's wireless communications became crucial historical testimony.

Inspired by this story and want to learn Morse code yourself? Our 7-day beginner's guide provides a structured approach that has helped thousands master this life-saving skill.

The Legacy

The Titanic disaster fundamentally changed maritime wireless regulations. Within months, new laws required:

• 24-hour radio watch on all passenger ships • Sufficient wireless operators to maintain continuous coverage • Regular lifeboat drills and sufficient capacity for all aboard • Standardized distress procedures

Jack Phillips' sacrifice didn't create these changes alone, but his dedication—staying at his post until the end—became a powerful symbol of duty that influenced maritime safety reforms for generations.

Today, when we use Morse code translators like MorseBuddy, we're engaging with the same communication system that saved those 705 lives on April 15, 1912. The simple elegance of dots and dashes proved its worth in humanity's darkest maritime hour.

Want to explore the mathematical principles that make Morse code so efficient? Read our article on the mathematics behind Morse code to understand how frequency analysis and variable-length encoding create an elegant communication system.

Conclusion

The story of the Titanic's wireless operators reminds us that technology alone doesn't save lives—it's the humans operating that technology, making split-second decisions under unimaginable pressure, who make the difference. Jack Phillips and Harold Bride weren't just telegraph operators; they were the thin line between hope and despair for hundreds of souls in the freezing Atlantic.

Every time those dots and dashes pulsed out into the darkness—"CQD CQD SOS DE MGY"—they carried more than information. They carried hope.

Today, as you explore modern applications of Morse code, remember that this "outdated" communication system once meant the difference between life and death for 705 people. The telegraph keys may have fallen silent on the Titanic, but the legacy of that night's Morse code messages echoes through maritime history, reminding us of the power of communication and the courage of those who kept transmitting until the very end.

Ready to start your own Morse code journey? Visit MorseBuddy.com to use our free translator and begin learning this timeless communication system that continues to save lives and connect people across the globe.

References

[1] Encyclopedia Titanica. "Jack Phillips: Marconi Wireless Operator." Available at https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/titanic-biography/jack-phillips.html

[2] Butler, Daniel Allen. Unsinkable: The Full Story of the RMS Titanic. Stackpole Books, 1998.

[3] Lord, Walter. A Night to Remember. Henry Holt and Company, 1955.

[4] Wade, Wyn Craig. The Titanic: End of a Dream. Penguin Books, 1986.

[5] British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. Report on the Loss of the SS Titanic. 1912. Available at https://www.titanicinquiry.org/BOTInq/BOTReport/botreprt.htm

[6] Marconi Company Archives. "Wireless Telegraph Operations, 1912." Science Museum London. Available at https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/marconi

Additional Resources:

• National Archives UK. "Titanic: Ice Warnings, April 14, 1912." Available at https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/titanic/

• Lynch, Don and Marschall, Ken. Titanic: An Illustrated History. Madison Press Books, 1992.

• MorseBuddy.com. (2026). "Free Online Morse Code Translator with Audio Playback." Available at https://morsebuddy.com/