The Mathematics Behind Morse Code: Why Dots and Dashes Are Brilliant

When Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail developed their telegraph code in the 1830s, they created something far more sophisticated than a simple communication system. They built an elegant mathematical solution to a complex optimization problem—one that wouldn't be formally understood until Claude Shannon developed information theory over a century later. The mathematics underlying Morse code reveals principles of efficiency, probability, and encoding that remain relevant in modern computing and communications.

Let's explore the mathematical brilliance hidden within those dots and dashes.

The Frequency Analysis Foundation

The most remarkable mathematical insight in Morse code is its use of frequency analysis—a principle that assigns shorter codes to more commonly used letters. Morse and Vail accomplished this by a remarkably simple method: they visited a newspaper printing office and counted how many of each letter appeared in the typesetters' cases.[1]

Here's what they discovered:

• E (the most frequent letter): · (1 unit) • T (second most frequent): - (3 units) • A (third most frequent): ·- (4 units) • Meanwhile, Q (rarely used): --·- (13 units) • And Z (also rare): --·· (13 units)

This wasn't random—it was optimization in action. By analyzing English letter frequency, they created a variable-length encoding where transmission time directly correlates with letter usage. The mathematical elegance here is profound: minimize the expected transmission time across all messages.

Curious about how Morse code encodes different letters and characters? Visit our Morse code alphabet page to see the complete reference chart and understand how frequency analysis influenced the code design.

Variable-Length Encoding: The Mathematical Challenge

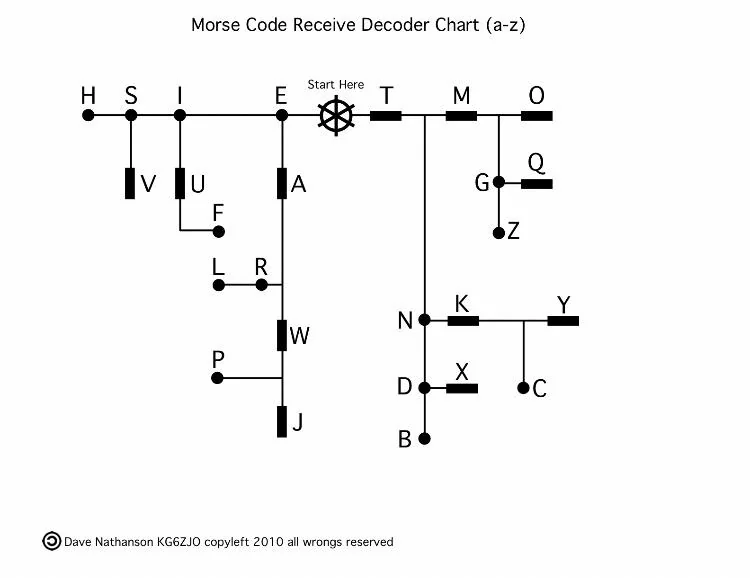

Morse code belongs to a class of encoding systems called "variable-length codes." Unlike fixed-length systems (where every character uses the same number of symbols), variable-length codes face a critical mathematical challenge: how do you know where one character ends and the next begins?[2]

Morse code solves this elegantly through timing:

• Dot duration: 1 time unit • Dash duration: 3 time units • Space between symbols within a character: 1 unit • Space between letters: 3 units • Space between words: 7 units

This timing structure creates a self-synchronizing system. The pauses between letters serve as unambiguous delimiters, preventing confusion. Mathematically, this is similar to the concept of "prefix-free codes" or "instantaneous codes"—no valid code is a prefix of another, allowing real-time decoding without ambiguity.

Want to see how Morse code timing works in practice? Try our free Morse code translator to encode messages and listen to the audio playback, which demonstrates the precise timing relationships between dots, dashes, and spaces.

Information Theory Meets Morse Code

When Claude Shannon published his groundbreaking paper "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" in 1948, he formalized concepts that Morse code had intuitively implemented.[3] Shannon's entropy formula measures the information content in a message:

H = -Σ(pi × log₂(pi))

Where pi represents the probability of each character appearing.

For English text using standard letter frequencies, Shannon calculated that each letter contains approximately 4.22 bits of information on average. Remarkably, Morse code comes surprisingly close to this theoretical optimum.[4]

Researcher John D. Cook analyzed Morse code efficiency by calculating the weighted average code length (frequency × code length for each letter). He found that the average Morse code letter requires 4.53 time units. When compared to an optimal rearrangement of the same codes, Morse code achieves approximately 91% of theoretical maximum efficiency—an impressive feat for a system designed 120 years before information theory existed! [5]

Interested in learning more about the history of Morse code and how it evolved? Read our comprehensive article on the complete history of Morse code to understand the full context of this mathematical achievement.

The Binary Connection

While Morse code predates binary computing, it's fundamentally a binary system: signal or no signal, on or off. However, it differs from modern binary encoding in a crucial way—it uses three states:

• Dot (short signal) • Dash (long signal) • Space (no signal)

This makes Morse code a ternary system in some analyses, though the dots and dashes themselves are binary in nature (just different durations of the "on" state).[6]

A more efficient pure binary encoding of Morse exists: represent a dot as "01" and a dash as "11", with "00" serving as the letter separator. This encoding captures all information while being completely self-synchronizing—you can start decoding at any point in the stream.

Compression and Redundancy

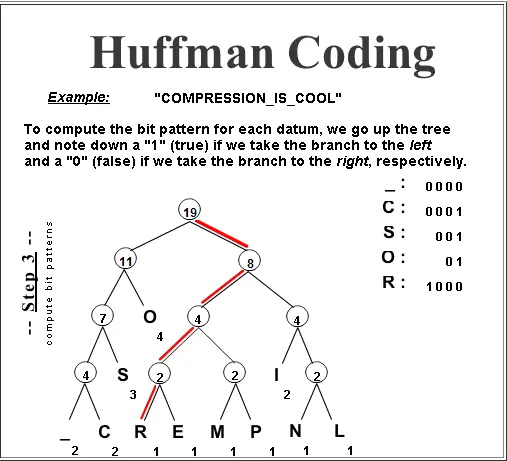

Modern data compression algorithms like Huffman coding and arithmetic coding use the same principle Morse code pioneered: assign shorter codes to more probable symbols and longer codes to rarer ones. This is mathematically provable to approach Shannon's entropy limit.[7]

Morse code also incorporates redundancy—the concept that not all bits in a message are equally informative. In English text, certain letters predictably follow others. For example, "Q" is almost always followed by "U." Shannon demonstrated that considering these relationships, actual English text contains only about 2-3 bits of information per letter when context is included, far less than the 4.22 bits for individual letters.

Morse code doesn't explicitly exploit these inter-letter dependencies, but its variable-length nature still provides significant compression compared to fixed-length alternatives.

Want to explore practical applications of Morse code in modern technology? Check out our article on 10 practical modern uses for Morse code to see how these mathematical principles continue to be relevant today.

The 3:1 Ratio: Mathematical Precision

The standard Morse code ratio—dashes are three times longer than dots—isn't arbitrary. This 3:1 ratio represents a mathematical balance:[8]

• Large enough to be reliably distinguished by human operators and simple equipment • Small enough to maintain reasonable transmission speed • Optimal for human perception and production

Experiments with different ratios show that deviating significantly from 3:1 increases error rates. Go too low (2:1 or less), and dots and dashes become confused. Go too high (4:1 or more), and transmission becomes unnecessarily slow. The 3:1 ratio sits in a mathematical "sweet spot" for human-machine interaction.

Probability and Error Detection

Morse code's structure also provides implicit error detection capabilities. Because legitimate Morse sequences follow specific patterns, random errors often produce impossible or highly improbable combinations. An experienced operator can detect when received code doesn't match expected patterns—a form of probabilistic error detection.

Modern error-correcting codes formalize this concept through mathematical redundancy, but Morse code's structure provides a similar benefit through its carefully designed symbol set and timing relationships.

The Scrabble Connection: Mathematical Consistency

Interestingly, Scrabble inventor Alfred Butts used similar frequency analysis when assigning point values to letters—more common letters earn fewer points. Statistical analysis shows strong correlation between Morse code length, English letter frequency, and Scrabble tile distribution.[9]

This consistency across different systems validates the underlying mathematical reality: English letter frequency is not arbitrary but follows predictable patterns that can be mathematically exploited for efficiency.

Ready to start learning Morse code yourself? Our 7-day beginner's guide provides a structured approach to mastering this mathematically elegant communication system.

Modern Relevance: Variable-Length Codes Today

The mathematical principles pioneered by Morse code live on in modern technology:

• UTF-8 encoding: Common characters use fewer bytes • MP3 compression: More common audio patterns use less data • Video codecs: Frequently occurring visual patterns are encoded more efficiently • QR codes: Error correction based on information theory

All these technologies trace their mathematical lineage back to the same principles Morse code implemented nearly two centuries ago.

Conclusion: Accidental Mathematical Genius

What makes Morse code's mathematics so remarkable is that Morse and Vail achieved near-optimal efficiency through empirical observation and practical testing, not rigorous mathematical analysis. They created a system that would later be proven mathematically sound by Shannon's information theory.

The dot-dash encoding, variable-length structure, frequency-based optimization, and self-synchronizing timing all combine to create a system that's mathematically elegant, practically efficient, and remarkably resilient. Even 180 years after its invention, Morse code stands as a testament to how good engineering intuition can arrive at mathematically optimal solutions.

Today, when you use MorseBuddy's translator to encode messages, you're engaging with a mathematical system that anticipated concepts of information theory, data compression, and efficient encoding by more than a century. The dots and dashes aren't just signals—they're an elegant mathematical solution to the problem of efficient communication.

Experience the mathematical elegance of Morse code firsthand. Use our free online translator to encode your messages and hear how frequency analysis and variable-length encoding create an efficient communication system that remains relevant after nearly two centuries.

References

[1] LessWrong. (2023). "Shannon's Surprising Discovery." Available at https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/GveDmwzxiYHSWtZbv/shannon-s-surprising-discovery-1

[2] Wikipedia. (2001). "Morse Code: Binary Encoding." Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morse_code

[3] Pierce, J. R. (1973). "The Early Days of Information Theory." IEEE Transactions. Available at https://jontalle.web.engr.illinois.edu/uploads/537.F18/Papers/PierceEarlyDaysInfoThy.73.pdf

[4] Cracking the Nutshell. (2013). "Information Theory: Claude Shannon, Entropy, Redundancy, Data Compression, Lossy vs. Lossless." Available at https://crackingthenutshell.org/what-is-information-part-2a-information-theory/

[5] Cook, J. D. (2017). "How Efficiently Does Morse Code Encode Letters?" Available at https://www.johndcook.com/blog/2017/02/08/how-efficient-is-morse-code/

[6] Reddit /r/explainlikeimfive. (2023). "ELI5: How Come Binary and Morse Code, Both Systems with Only 2 Options, Can Work So Differently?" Available at https://www.reddit.com/r/explainlikeimfive/comments/18be98o/eli5_how_come_binary_and_morse_code_both_systems/

[7] Science4All. (2016). "Shannon's Information Theory." Available at http://www.science4all.org/article/shannons-information-theory/

[8] Djavaherian, L. (2017). "Morse, Decoded: A Simple Hand-Sent Morse Decoding Algorithm." Available at http://greatfractal.com/MorseDecoded.html

[9] Richardson, M. (2004). "Morse Code, Scrabble, and the Alphabet." Journal of Statistics Education, 12(3). Available at https://jse.amstat.org/v12n3/richardson.html

Additional Resources:

• Cook, J. D. (2022). "Varicode: Variable Length Binary Encoding." Available at https://www.johndcook.com/blog/2022/03/01/varicode/

• 101 Computing. (2024). "Morse Code Using a Binary Tree." Available at https://www.101computing.net/morse-code-using-a-binary-tree/

• NTU CMLab. "Variable Length Codes." Available at https://www.cmlab.csie.ntu.edu.tw/cml/dsp/training/coding/vlc/

• NRICH Maths. "Inspector Morse." Millennium Mathematics Project. Available at https://nrich.maths.org/problems/inspector-morse

• MorseBuddy.com. (2026). "Free Online Morse Code Translator with Audio Playback." Available at https://morsebuddy.com/